The new Chineseness: great leap forward or backward?

Looking backward is a major trend in Chinese fiction today - writers often set their novels in the past to reflect on Chinese history and culture. In this genre, Mo Yan’s Sandalwood Impalement (Tanxiang Xing) is not only a commercial but an ideological hit, praised by critics as a ‘masterpiece’ of ‘historical importance’ that shows China can overcome Western influence thanks to ‘Chinese tradition, Chinese reality, and Chinese mentality’ as apposed to vapid ‘universalism’ and ‘humanism’.

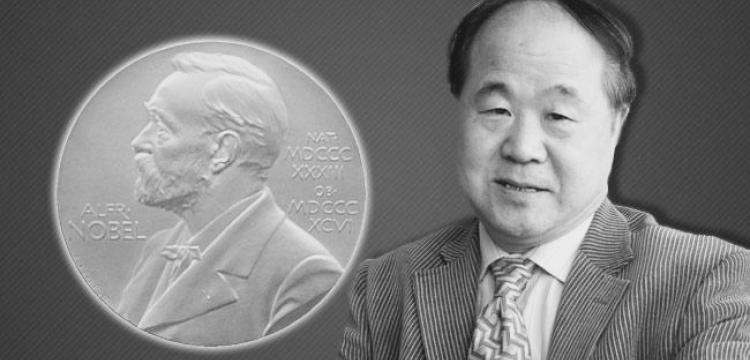

The Nobel literature prize laureate Mo Yan (Don’t Speak, a pen name) gained fame in the late 1980s for his ‘lavish’, ‘wild’, ‘backward’ style. The filmmaker Zhang Yimo based his prize-winning movies - Red Sorghum (1987) and Ju Dou (1990) - on Mo Yan’s novels, making the author well-known internationally as well as a bestseller at home. In his novel Sandalwood Impalement (2001), Mo Yan developed his style to the utmost and declared his return to Chinese tradition.

Like most writers who came of age after the Cultural Revolution, Mo Yan read foreign literature in translation. His earlier works got wide circulation in the West thanks to his ‘incorrect’ view of Chinese society and history; many in China, however, remarked that he pandered to perverse Western interest. Some said that he bartered China’s dignity for personal fame; he even got into trouble with the PLA. But not any more. An unorthodox writer going back to his roots at peak career confirms Chinese public opinion that their civilization is matchless. Chinese are ethnocentric and always have been, but confidence makes ethnocentrism strident. Confidence about the future makes Chinese candid about the past - they can afford to be because they feel strong now.

Sandalwood Impalement is truly ‘made in China’. It bustles with noise and activity like a Chinese funeral - weeping and wailing followed by loud music and a banquet. The story takes place around 1900 in a Shandong peninsula village where the Germans are building a railway through farmland. The Qing government, under pressure from Germany, is on the hunt for a rebel sect leader who kills Germans. He is finally caught and publicly impaled on a sandalwood stake.

The main characters all depend on and interfere with each other. Their interwoven family conflicts are typically Chinese; the logic is transparent to native readers. Mei Niang, the heroine, is a beautiful young woman who runs a dog meat eatery; her nickname is ‘Dog Meat Beauty’. She is ambivalent toward her father, Sun Bing, a leading cat tone (maoqiang) opera singer and womanizer. Her mother died when she was little, so she was brought up by her father. Due to his negligence, however, her feet were never bound, and because of her ‘big’ feet (she envies women with bound feet) she has to marry Xiao Jia, a simpleminded butcher she does not even like. Sun Bing hits and accidentally kills a German railway technician he sees sexually harassing his young second wife. In response, German soldiers kill his wife, children, and neighbours, so he organizes ‘boxer’ rebels to retaliate. He dresses up like the Song general Yue Fei (1103-1142) and believes he is possessed by Yue’s spirit, making him invulnerable to blades and bullets.

Mei Niang’s lover, Qian Ding, is a local bureaucrat - an elegant, learned, married man. She is passionately in love with him because he gives her everything - sex, respect, culture, psychological support, and expensive presents. Her husband tolerates (even encourages) Mei Niang’s extramarital affair because it augments the family income. Qian Ding, under orders from the central government to arrest Sun Bing, does what he is told in order to keep his job. One day a stranger who claims to be Xiao Jia’s father comes to Mei Niang’s home. Xiao Jia adores his ‘father’, Zhao Jia, China’s chief executioner sent by the Dowager Empress and General Yuan Shikai to devise a cruel and unusual punishment for Sun Bing, who has to suffer five days and nights and die during the opening ceremony when the first German train rolls through.

Trains and cat tone opera are the two pillars of the novel. The story turns on superstition about trains. When village people first saw trains, they thought they were monsters that could run without eating because they absorbed energy from the tracks laid on ancestral graves, disturbing fengshui. They believed the Germans conscripted young boys, trimmed their tongues to make them speak an alien language, cut their queues to steal their souls, and buried the queues under the tracks to ‘feed’ the trains. They were also convinced that bad fengshui and this theft of young souls caused poverty, disaster, war, and misfortune. Cat tone (a local opera that mimicked cats yowling) was performed at funerals, weddings, and religious festivities. It was unique to Mo Yan’s home village and an integral part of local life until the 1980s, when it died out because of modern entertainment. Mo Yan structures his novel like a cat tone opera, quoting opera lyrics and using cat tone sounds to signify strong emotions.

The novel resembles a folk opera: passionate and sensual. It has vivid colors, sounds, images, even smells. The execution scenes are graphic: over ten thousand words describe decapitation, death by slicing, and impalement. Sounds are piercing: gossip, scolding, singing, trains roaring, cats yowling. One can smell not only the scent of cooked dog meat and rice wine, but also the stench of body odor, vomit, urine, and excrement. The language is peppered with dialect, slang, and old folk opera lyrics. Mo Yan’s fictional world is the antithesis of refined Confucian society; it is also ‘unpolluted’ by Communist ideology or Western values. It is exactly this ‘backwardness’ that charms many Chinese. Without it, the novel would read like cliché anti-colonial class-struggle stories that often appear in Communist history textbooks.

Mo Yan spent five years writing Sandalwood Impalement, and the language and plot show the effort he invested. The effect, however, is strictly lowbrow. The roots of the Chinese novel lie in street storytelling and folk opera; Mo Yan deliberately returns to these roots. Chinese novels from before the New Culture Movement of 1919 are almost all third-person narratives about conflict and intrigue - their main function is to entertain. Sandalwood Impalement is closer to traditional novels of three and four hundred years ago than to new novels since 1919. Mo Yan himself calls this book a great leap backward - it is a declaration of war on both highbrow intelligentsia writing that imitates Western fashion and consumerist yuppie writing that panders to a public eager for sensation. The great leap backward wins applause from Chinese readers and critics who are confident of their civilization and proud of its resurgence.

Critical acclaim for Sandalwood Impalement owes to cultural nationalism, not literary excellence. Ideology outweighs art. Despite being carefully plotted, structured, and written, the novel does not rise above artisanship. The urge to recreate an authentic China is detrimental to creativity. Compared with Mo Yan’s earlier novels, Sandalwood Impalement is contrived. It is a skilful imitation of folk opera - a splendid street performance full of sound and imagery, leaving nothing to the imagination.

Cultural nationalism does even more damage to literary criticism, supplanting aesthetic appreciation with moral judgment. Moralizing has always been a weakness of Chinese literary criticism. Today, when Chinese writers enjoy freedom of expression, critics are conformist. They conform not to any official line, but to public opinion, which (if anything) is more chauvinist than the government. Chinese readers have good reason to dislike highbrow intelligentsia writing that is often a clumsy imitation of Western literature. They also have good reason to disdain consumerist yuppie writing that is often mawkish, affected, narcissistic, and sensational. But a return to folk tradition is no cure for bad writing.